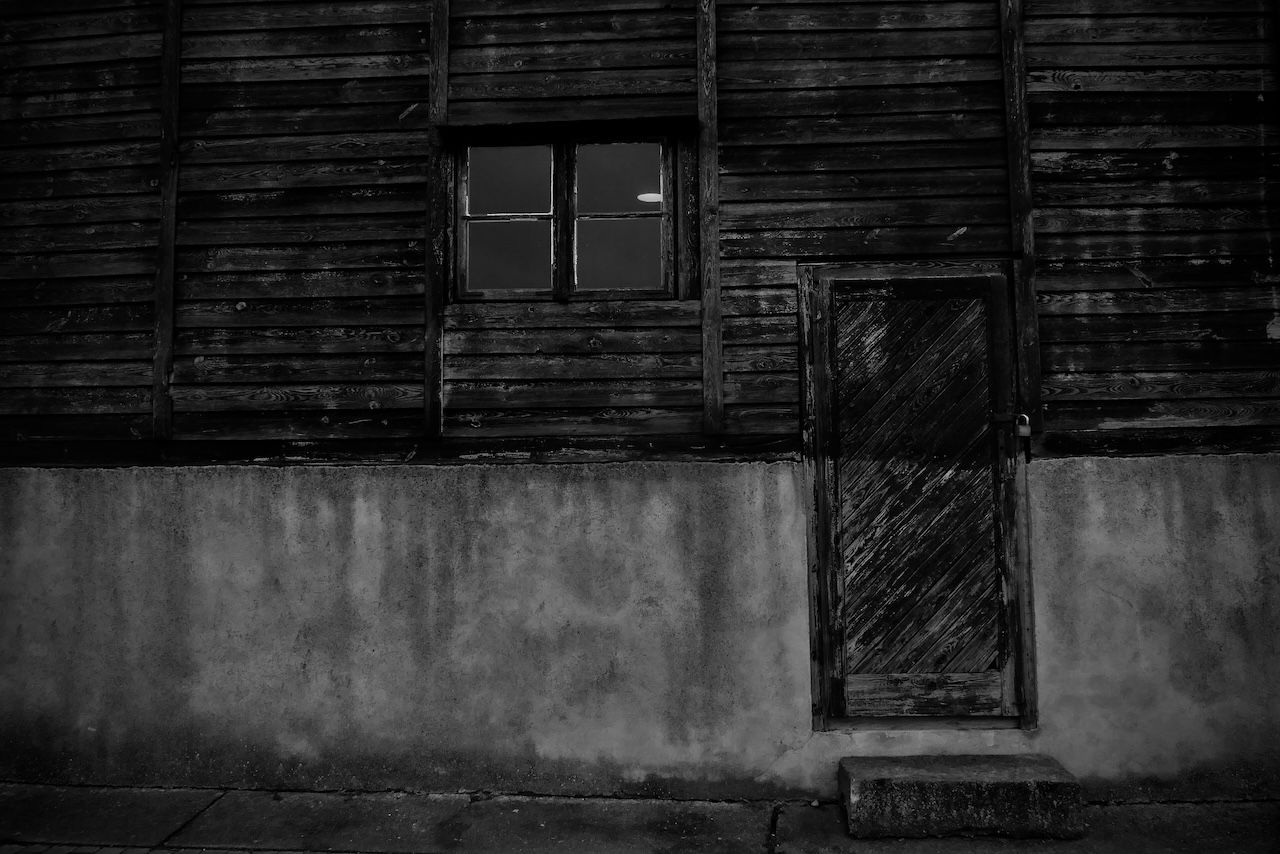

My first visit to Majdanek was on a boiling hot August afternoon. My second, a freezing cold November morning. Regardless of the temperature extremes, there is something uniquely consistent about the place: it has a mournful, laconic atmosphere that penetrates right to one's core.

To accompany my photography, I have chosen the testimony of Sonia Warshawski. Her words portray the evil sadness of Majdanek in a way I simply could not attempt.

Sonia Warshawski grew up in Międzyrzec, Poland. She was 17 years old in 1942, when the Germans forced her and her family into the ghetto where she worked as a slave laborer. When the ghetto was liquidated, Sonia and her mother were deported to the Majdanek death camp. Her mother did not survive. Sonia was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and then to Bergen-Belsen where the British liberated her. At the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp she met her husband John. The couple moved to the USA in 1948.

Sonia Warshawski Testimony Transcript.

I’m Sonia Warshawski – my maiden name, Greenstein. Our hometown’s name is Miedzyrzec in Polish in Miedzyrzec, Polaski and in Yiddish - it’s Mezritch.

Before the war it was really a very cultural Jewish town you call it on its size. And more or less we had a lot of freedom, as far as, you know, in the Jewish affairs. Our hometown had a very, very wonderful Jewish youth and a very high intellectual. And our, we were three children at home, and I’m the only one, I am the survivor and my sister in Israel, we are two survivors. My mother was taken to Treblinka. My father and my brother was shot. So I am the only one and my sister are survivors in our family, except a few cousins.

Majdanek

We had a very normal - normal life and a lot of laughter and I went school – a public school which was mixed, you know, Jewish and Catholic. And the majority was Catholic, naturally. And each - give you an idea how in school - which here is not permitted in school saying prayers, we had to stood every morning and do the prayers which the Catholic children were reciting. And each class had Jesus Christ on the wall. And so it always remind us that we’re outsiders. Although we did have like once a week, you know, a Jewish teacher – teaching us about our religion, you know, and history. And getting more acquainted more with our history – our Jewish history - we most of our Jewish youth belonged to organizations – organizations which were most of them aiming for a future to be in Israel.

This was something for me very important that we came always to this – to the meetings – and the history of our, you know, the Jewish history was very important to us and it gave us a lot of courage and encouragement.

And our hometown was first the Russians came. And then, I don’t know in history if you recall – Stalin and Hitler had a – they arranged a different borders.

So our hometown went through a trauma. After the Russians backed off, the Germans came in. And I want you to know, before the Russians left you could go with them and they were already kind of warning you, you know, what you can expect when the Germans will come, because we knew already what was happening in Germany.

But we did stay behind. Some lotta, lotta Jewish people went with the Russians and they survived – most of them survived in Siberia. When the Russians were asking, you know, everyone, you could go with them. The only thing you could not take any belongings really - like from your house, home, you know, furniture and so on. And my father really foresaw things and he was begging my mother that we don’t need anything just a little, a little, you know, small little trunk – whatever you call it – and a few belongings.

So, anyway, when the Germans - when the SS took over, then the killings started. They took out – the first thing went, you know, the rabbis. They put them through the streets and they killed them later. The beards, were you know, torn off. It was, it was, horrible.

And little by little they started to – let’s say, where we were living - we had to move – we moved first to my grandma’s place and from there they did it gradually to get, to put us in the ghetto, but not right away because it took time – some time. So, in the beginning, then we moved again to what they call it – dzielnice żydowska– that means it was open. It was not a ghetto yet.

But certain streets, there only Jews were living. And so, we knew that something horrible is coming. And we had to, of course, have our, you know, yellow arm bands – whatever you call it, you know, as a Jew. You couldn’t be at certain times on the street. In the meanwhile, everyone had to have a job. You had to be, you know, to survive, you had to work. You had to have a permit, you know, that you are working someplace. Since our city, I want to point it out, was a very industrial city, we had our brushes – brushes and fur and leather.

Our brushes were going all over the world – were shipped. So, thanks to that, our, you know, our hometown was surviving much longer than many others. So, I was working in one of those brush factories and my father was also having a job in a different, you know, factory when the first deportation took place in our hometown.

There was not a ghetto yet – it was still an open ghetto.

At that time, you know, when all the Jews had to go out to the marketplace and sitting there, I went but my father and my mother and my sister, they went into hiding. I went because I knew that I had this ah – since I was working – and I had this paper that, you know, I am working – that I will be saved. And my brother was, at that time already – thanks to my father – you know, through connections, he was already working in a – um – it’s a engineering place – so we both went to this, you know. And while they were calling off our names – whoever worked in the factories – he just took off his armband, you know, and he just walked off. He was a very heroic, you know, young man. And walked off there was the, the a, main - not public house – but city hall. City Hall was right by that marketplace, you know. And he hided there. So when I went back to the factory after they took us out, I was in the attic watching looking through when they were rushing our people to the trains. They rushed them – not only eh – they were rushing them so fast, they had to run, run. Whoever couldn’t run, they were shooting. The shootings were – till even now – I could hear the shootings – shooting babies – shooting elderly who, you know, whatever it was in August –it was already, you know, very hot. And this was 1942 – August the 25th – something like this. After this, you know, deportation, I still had my family.

[My parents] were hiding – it was a neighbour had a um - a house - and between the house and another house there was a very tiny alley and they closed it up and they were hiding there.

They survived this, you know, deportation. And though, you know, the ghetto was found. We moved to a one little room that only two beds could be, you know, be standing there. Actually, one bed and one was a couch, actually. And we had a little table – and very lucky that we had a little stove – a tiny stove I think to, you know, that you could cook on two platters.

And I was still in the factory – walking out from every day. And my brother was – since he had his job outside of the ghetto – he did not – he only came in but overnight they stayed in a special place – all of those boys, with this, you know, Polish engineer. So, thanks to him, it was a big help, you know, he could bring us in sometimes, you know, some food, and so on.

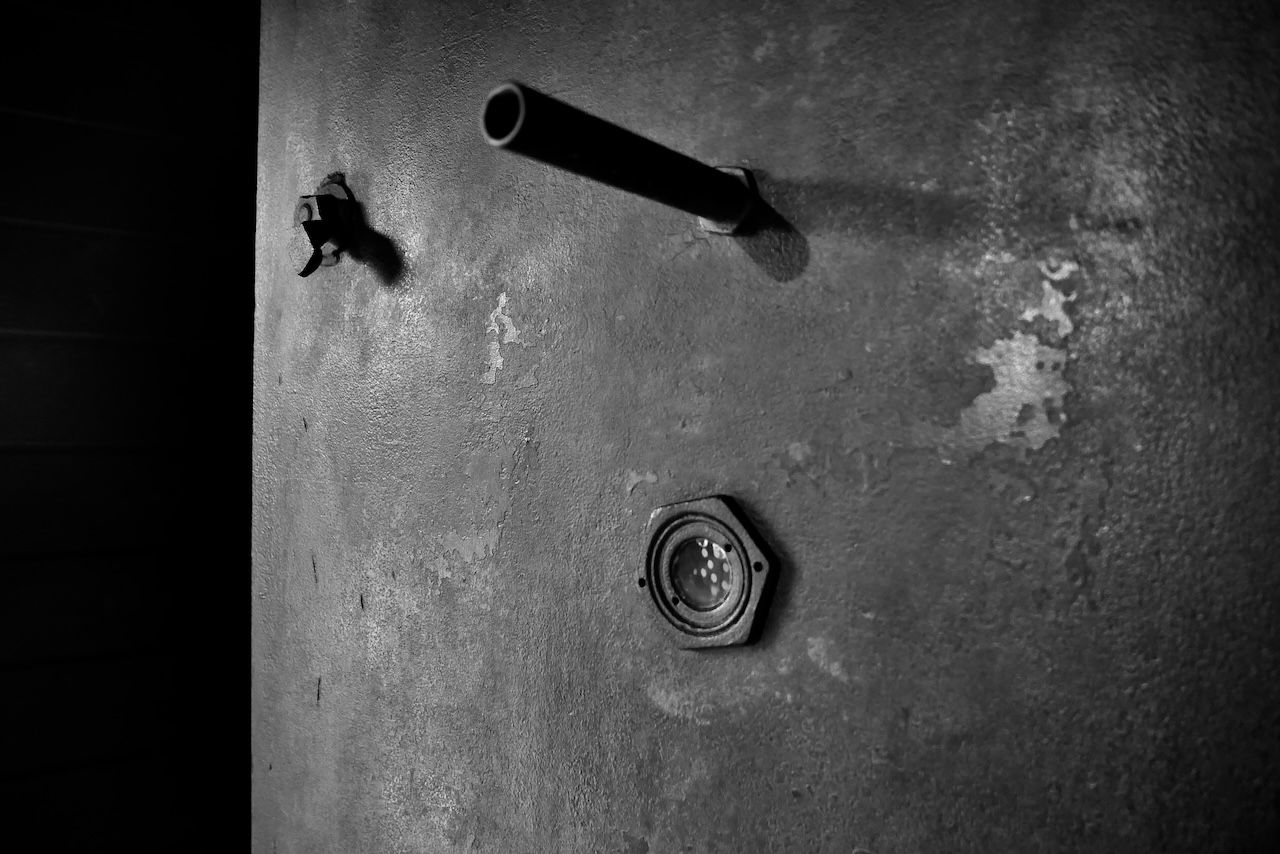

The Gas Chambers | Majdanek

The situation, you know, it was in the ghetto very horrible. One night I remember one it was on like New Years – they just came in, in the ghetto and just for fun killing from right to left - just went in and kill everyone who was in sight. So, you was always under that, you know, fear that maybe you will be next. So, we just, we knew that somehow end will come.

We digged up in our little place under the floor, we had a hiding place. We had to go in almost crawling under the bed and there was a opening and then we went in, you know. You could not stay many, many days there because there was not any air, but just in an emergency, we had this, you know, and that was important.

My sister, you know, when they took us out from our hiding, for this was another deportation, when they took us out this particular day for this other deportation, we had to kneel in the front of the house where they took us out and they were bringing also from different hiding places, some more of our people and while we were sitting there, the guards was watching us. And my little sister was sitting just next to my father and she was really falling apart.

She felt this is really it, they’re goin’ kill us, they’re goin’ kill us. And some point, when the guard was maybe at one second looking away, my father pushed my little sister. There was a little door to a little alley, pushed her and she escaped.

And then after we already got up to walk to the ah main, you know, again to the marketplace where more surrounded people my father escaped in the last moment. And keep in mind that my brother was not at that time. And this was May 3rd, 1943.

My, my brother was still outside of the ghetto. We knew that he’s, he’s still alive. So my brother took my little sister to a farm. And he paid some special, you know, money, for a whatever valuables for her to keep her. And he used to come each week and check on her.

In meanwhile when they killed my brother and my father were in hiding – they were hiding also in a attic – at a Polish, you know, house and someone gave him up. They came and they shot my father and my brother. And when the farmer – the lady- the farmer got the news that he is not alive, they threw her out. When they threw her out she was by herself in the forest. She was walking miles and miles until she came upon a very big partisan group, which were really already the Russians – they escaped from the German’s prisons.

So she survived with them.

After they took us out from the hiding and we knew that, like I mentioned to you about my father and my sister, it’s only me and my mother where in – this was May the 3rd, exactly my brother’s birthday – was on May the 3rd. We were also taken again to the, you know, to the marketplace and from there after the ghetto, I don’t know how many still thousands of people, we were loaded.

We walked to our train. They put us, probably, I don’t know how many, it was just like herring, they packed us in those, you know, cars in the train. And each boxcar had a very little bitty window – okay. And it was, you know, with wire. It was so packed and hot inside, that lot of the people were dying. I can recall when we went to one on a station at night, you know, we stayed there for several hours, the thirst was so tremendous that lot of the people were dying just for thirst and the heat. I was just a short little girl. I was wearing some boots and we all had always prepared that I had some money in the boots if something happened. And I was standing on corpses to reach this little, you know, this little window, that I could just only bare one hand with my money stacked in my hand to give it to the Polish, you know, what they wear by the train workers, whatever. And he hand me over one – how do you call it - the Boy Scouts have it too – a canteen, yes. And he gave me a canteen with that water.

As soon I pushed in that little canteen and I wanted just a give a drink and give it to my mother - barely you could do it because everyone was dragging that canteen from you, you know, to get this.

Women's Bathroom | Victims Belongings

And by the way, when um this particular train when I was on with my mom – it was going to Treblinka. Since Treblinka was so busy and the trains were still sending kilometers and kilometers they turned our train to Majdanek.

When we came to Majdenek – what a sight! They were selecting people right there while we were going, you know, beating us, you know, rushing out from the, from the train. And right there they were shooting the old, elderly, and children, as many, you know, as they could. And then they took us to the shower room, you know, where they gave us a bath. And I was still with my mother and they took all our clothes and everything – belongings, you know, belongings – we didn’t carry any belongings – just what we had on our body and there we were in Majdanek. I was with my mother in Majdanek. Majdanek had a gas chamber, I want you to know. And some of the people, after the selection, where they didn’t got killed, they finished them off in the gas chamber.

While in Majdanek we came – I was there since May the 3rd – till late fall. This was a camp which we went through selections, naturally, and we worked on the fields. You had to always, you know – you had to work – let’s put it this way. And we um either on the fields or you carried the ah – at that time they didn’t even have latrines, regular latrines, because the camp really was not organized really the way it should. So they had only holes and dysentery was dysentery that the way you pronounce it was, you know, it was there. And I had dysentery there where I was. And if not my mother, I wouldn’t have survived, because lots of times the only thing when you have this, you want to drink more water and more water. And more you drink that will be the end of you. So she was holding me back and tried to - like we had a lot of still Polish, you know, Catholic girls in this camp - which they were allowed to get packages from, from homes, from their homes. And so she used to trade in like piece of bread maybe for a little piece of fruit or something, a little piece of cake or something like this. And thanks to her I survived the dysentery there.

This was Majdanek.

While we were there, there were in particular two girls which they tried to escape and they got caught. Those girls one evening we had to stay all, you know, in rows. It’s like all four angles, okay and this was in the middle of the guillotine. Now I’ll never forget this in my life, were like two girls, you know, carrying their little stools to the hanging. And we had to watch this.

I remember when my mother was turning her head, the SS woman was going around and she slapped her face that you, you know, you had to watch it. And while those girls were hanging in their last breath they were crying to us not to forget, and take revenge.

So to the end of the summer, there was another big selection, and you had to take off your clothes completely and this was outside – the selection was taking place. When I came with my mother in front of him – he sent my mother to the left and me to the right. I don’t know if you know what it means. The left was always to your death and the right was still maybe hoping to another camp or again, you know, to work. So my mother was taken away from me. And they sent me on the right side which was supposedly to go to Birkenau – Auschwitz-Birkenau.

While this after the selection they took us all the girls who were to go to Birkenau- Auschwitz to another field. And we stayed overnight, I’ll never forget this in my life, this particular barrack, and in the morning they made a blocksperre. A blocksperre meant everybody had to be inside. And they, you know, usually with a big whistle, you know, they let you know you had to be all inside. When this happened we knew always something is occurring.

So I want you know this was all the women who they were select to their day of death to go to the gas chamber, were marching from that field where I was before and I was very curious. I went, you know, to the ah, to the big door what we have in this particular barrack, and I put only just a little space open and to look and this was, you know, my last vision of my mother, when she walked to her death knowingly with another lady I’ll never forget from my hometown too. They were kind of holding each other also, you know, in rows of five. So this was the night that I really fell apart. Before the next day they send us, you know by the trains to Birkenau-Auschwitz.

So this was, you know, I lost my mother there.

The next step was, you know, Birkenau- Auschwitz. When we came to Birkenau- Auschwitz, they put us like in a quarantine they called it so. In this quarantine, we stayed for I don’t know for how long and the only work we did there is something to finish you off – like you carry today the stones, you know bricks from here to another place, you know, and that’s what.

And after this I was selected to another barrack, which was Kommando 22, and this Kommando was we were working in the fields in the summer and in the winter - I also want to tell you that when we came there, they usually what they did even when you went through a ante-lousing that means this when you took the showers they gave you clothes like for the summer in winter and in winter for, you know, vice versa.

So you had to always be on the ball and maybe through connections, through other girls, what they worked by the clothes someplace that maybe you could get an extra – a little sweater or something, because otherwise you wouldn’t make it. And so it was, it was very, very – like in hell over there. The rations you were getting a little soup with some kind of plant – I cannot tell you. Once in a while there was like Christmas, there would you will maybe fish out a little piece of potato. This was, you know, something very unusual. Their ration was like two slices of bread all day and sometimes they would give you just a little piece of margarine or little, you know, some kinda jello, I don’t know jelly or something. And this was your ration. Auschwitz-Birkenau was also you went through lot of selections. So I must went through about three, four selections.

In Birkenau I came end of, you know, from end of fall in 1943 and I stayed till 1945 in January. I stayed there till the Russians were nearing into Auschwitz-Birkenau. They took all of us who was able to walk – feeling in pretty good shape. We got one blanket and a ration of one can I think was some kind of meat, you know, horsemeat I think - yah, horsemeat and a portion of bread. I cannot tell you exactly if it was a half bread or a whole bread. And you know we had wooden shoes, naturally. And they took us – we walked for days and days and already in the snow.

After this they put us also in open cars, you know, cattle cars. And this was in the winter, mind you. And all we had was just one little blanket. And the snow was already falling. And we were driving in those, you know, with those trains, I don’t know, don’t ask me how many days. We probably went through all Germany.

We would see at night the flickers from the red, you know – those beaut... the homes. You can imagine our feelings if someone is sitting in a house – in a warm place. And in meanwhile, while it was taking place, this, you know, driving us, there was already lot of bombing. You know, the bombing from the Americans or the English, I don’t know. And we could, the bombs were, the bombing places were not too far from us, but for some reason, we didn’t care even if they bombed us.

Majdanek

But we went on until we came to ah finally, to Dachau. In front of the Dachau we were segregated like half of the women went to Bergen-Belsen and half of the women, whatever, went to Gross Rosen. I fell into Bergen-Belsen. When I came to Bergen-Belsen, I want you to know, Bergen-Belsen did not have a gas chamber. It had a crematorium. They did not need a gas chamber, because the typhus and the malnutrition they was so great that the girls was just dying like flies.

And, luckily, in Bergen-Belsen I fall in, was my luck, to work in not in the kitchen, because I was not strong, you know, enough in the shell – where – in the peeling room. It was just like also like a barn and you were peeling like all kind of rutabagas, mainly was the our, you know, and they had in piles, you know, in the front. I tried also even, they checked us before we went to back to the each evening ‘cause the kitchen, I want to explain to you, was outside of the – of the regular camp.

So we had to walk each evening back to that camp and then in the morning they brought us to that kitchen, okay. In the front, across from the kitchen, was the men’s camp. Bergen-Belsen was also like you – I don’t think they could send me anymore to hell because I was in hell already. You could see every day, columns, I mean just piles and piles of dead bodies. And the men, with themselves already, you know, looked like skeletons, and they were dragging all those dead people to the crematoriums. And we were lying on the floors there.

When at night if you had to go out to the latrine, you had to almost step in on some of the girls.

One day, when we were in – at work, we noticed that something is happening. We did not – we did not see that many SS women being there in the – in the kitchen where they usually guard us and the men also – SS men. So we knew something is going on and already whispers that the liberation is – someplace – not too far away. I was very curious. And I was sitting, right, you know, on a bench there with some other girls from friends – what I remember.

And we had what I explain to you it was like a barn at a very, very wide open like a door. And I was very uneasy. I said, “Ah, well, I will go out to the - ah latrine.” And you could have a larger, longer view, because Bergen-Belsen also a very big camp.

And while I was there looking out, because you could hear already the noise from the– from the earth. That something is coming like – how do you call it? – like the vibration – yes, the vibration of the tanks. You could hear tanks are coming. And I knew this must be the – our liberation. I was so excited until coming in back to my place, you know, to this the barn. And meanwhile, where does the hungry go. I mentioned to you before, the men’s camp was just across. They opened the doors – the gates – and they all were piling to the kitchen. So, while, you know, they were all piling, the guards were still guarding in front of the kitchen.

Sentry Posts | Majdanek

And I was trying, you know, the girls were very excited and I want to already tell them too that I have seen, you know, the tanks are coming and I was standing just like this and he was shooting from a very short, you know, distance and the bullet, you know, came in through here and came out through here – centimeter from my heart – centimeter from my lung.

In a meanwhile, outside, the English were already there and they had all of this women what I showed you here, you know. Can I show it? They were all standing, you know, out there on the platform and the main SS men who were around the camp – he was a all standing with their hands up.

And I’ll never forget in my life, when I got the bullet, you just don’t notice, you don’t know what’s happened to you. I just felt something like and I noticed blood is coming out of my and I didn’t even notice this place. I noticed that I have blood coming out of my mouth. I want you to know that I was drinking this blood, just thinking, “God, after I went through so much and the day here in Liberation, I have to perish.” In the meanwhile, one of the men, I’ll never forget, one of the Russian men who came in from the camp, one of our you know, inmates and he picked me up, and he took me to the, you know, to the window, in the kitchen. He said in Russian to me, “Look out and see before you die, the Liberation.” And then after this, he took me, they took me out on the front of the kitchen, this was, this was April the 15th in the Liberation Day. And it was still cold. They had to, you know, strip me and the first aid, the English doctor, from the army, gave me the first aid. And I was lying, I don’t know, how long on the soil, you know, on the ground until they took me to the camp.

And a meanwhile, I want to explain to you since this was in the camp, and the English, they had to move us from the typhus and from all of the, you know, dead bodies, that we went through a disinfection and a Red Cross car – eh trucks – took us to another destination, which was before – eh like Leavenworth here - an army, what you call it, barrack. Yeah, not prison, no, no, no. They were actually living there. You know, the soldiers, army, yes, army barracks.

And they were very, you know, nice buildings – actually, buildings – buildings and buildings – lot a buildings. And there, you know, we came. Some of the girls, like in my situation or they had or they were typhus or something – they were assigned to the hospitals, which the English, you know, were tending to it. And some of the girls where they were or the men, they were still already healthy enough, they were given, you know, places to live in those also – in those buildings.

Autopsy Room | Crematoria | Majdanek

Well, it’s hard to know really to define [how long I was in hospital], you know, how many weeks and weeks, you know, I was there – until I was able, you know, to walk out. And from there on, you know, life was still, you know, we were in a camp, like the DP camp, which you call it and the English, you know, they gave us provisions and clothes until you got on your feet and later on you went on your own.

After I left the camp, first I went, one man from my hometown showed up looking for, you know, for his sister and so on telling me – bringing me regards - my sister survived. So you can imagine this was my first, you know, thing to do. I went back to Poland, to my hometown. And this was just, you know, eerie, because the trains were not going, you know, normal – nothing. And we had to sometimes go with the Russian soldiers on trucks, you know, to for travelling. And it was very hard for you to understand how it was – really was. And there wasn’t any borders yet - nothing. And I came to my hometown after the war to see my sister. After I found my sister, I did not want to stay on in Poland. My hometown was, to me, like a ghost town. Wherever I was walking there I could – I could go back with memories from my family, memories from my friends, my girlfriends, you know – students from school. So it was too difficult. I didn’t want to, you know, stay on. But my sister stayed on and finally she – she did marry before I – I decided to go back with this idea that they will come later.

And I went back to the English zone to – to Bergen-Belsen. And there I met my future husband. After the camp Bergen-Belsen, you know, from the DP camp, I moved to – because my husband and his family, they went to Bad Nauheim – to the American zone, which was a better zone to go on looking on the future, if you wanted to get out of Germany. And our first child was born there. So when we came here, I was pregnant with my another child. We came here assigned to Kansas City from New York because, John’s, my husband’s, two sisters and brother were already here. So automatically, they sent us to Kansas City.

Source:

Sonia Warshawski Testimony

https://mchekc.org/portfolio-posts/warshawskisonia/

© Midwest Center for Holocaust Education

Original Testimony Video:

https://youtu.be/MzNBMP-GLTk