I strongly believe that as time passes, the importance of preserving the memory of historical events becomes increasingly vital. Of course, one such event (or series of events) that holds immeasurable significance is the holocaust, a dark chapter in human history that saw the systematic persecution and extermination of millions of innocent lives.

Visiting these sites not only allows me to pay tribute to the victims but also serves as a powerful reminder of the atrocities committed. And in recording these places, I hope that in some small way I am encouraging the memory of these victims and what happened during the holocaust.

At least that is my hope.

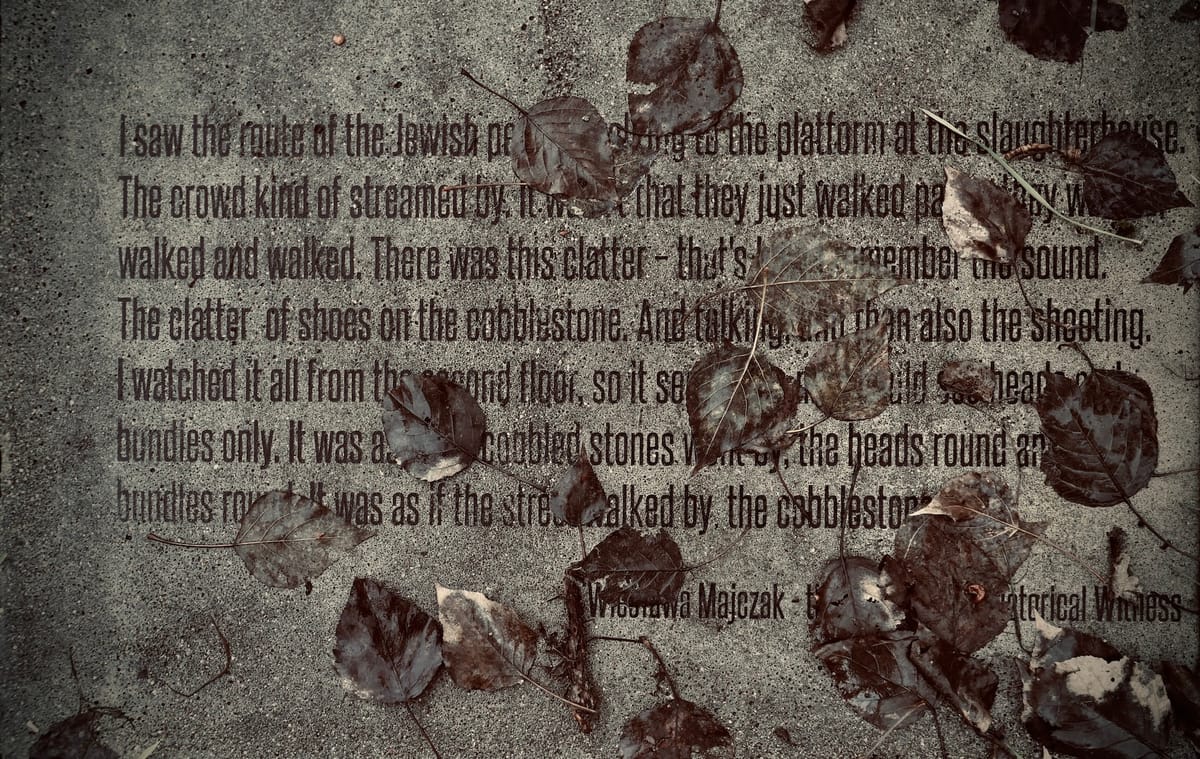

Yesterday, (20.11.2023) I visited Jósefów, about 40km south of Zamość in south eastern Poland. Now, Jósefów, like so mnay thousand other villages in this part of the world suffered it's own fair share of atrocities during the war, but it has gained some small notoriety for one event in particular. Let me explain.

In the early hours of July 13, 1942, men of Reserve Police Battalion 101, a unit of the German Order Police, entered the village of Jósefów. The unit had itself only arrived in Poland less than three weeks before, most of them recently drafted family men too old for combat, think service workers, artisans, salesmen, and clerks. By nightfall that day, they had rounded up Józefów's 1,900 Jews, selected several hundred men as "work Jews," and shot the rest in the forest on the outskirts of the village, that is, some 1,500 women, children, and old people.

Most of these overage, rear-echelon reserve policemen had grown to maturity in the port city of Hamburg in pre-Hitler Germany and were neither committed Nazis nor racial fanatics. Nevertheless, in the sixteen months from the Jozefow massacre to the brutal Erntefest ("harvest festival") slaughter of November 1943, these average men participated in the direct shooting deaths of at least 38,000 Jews and the deportation to Treblinka's gas chambers of 45,000 more - a total body count of 83,000 for a unit of less than 500 men.

Just over 81 years later, I found myself in the same village and the exact same secluded spot in the forest where the shootings took place. But I was not prepared for what I found there. Not at all.

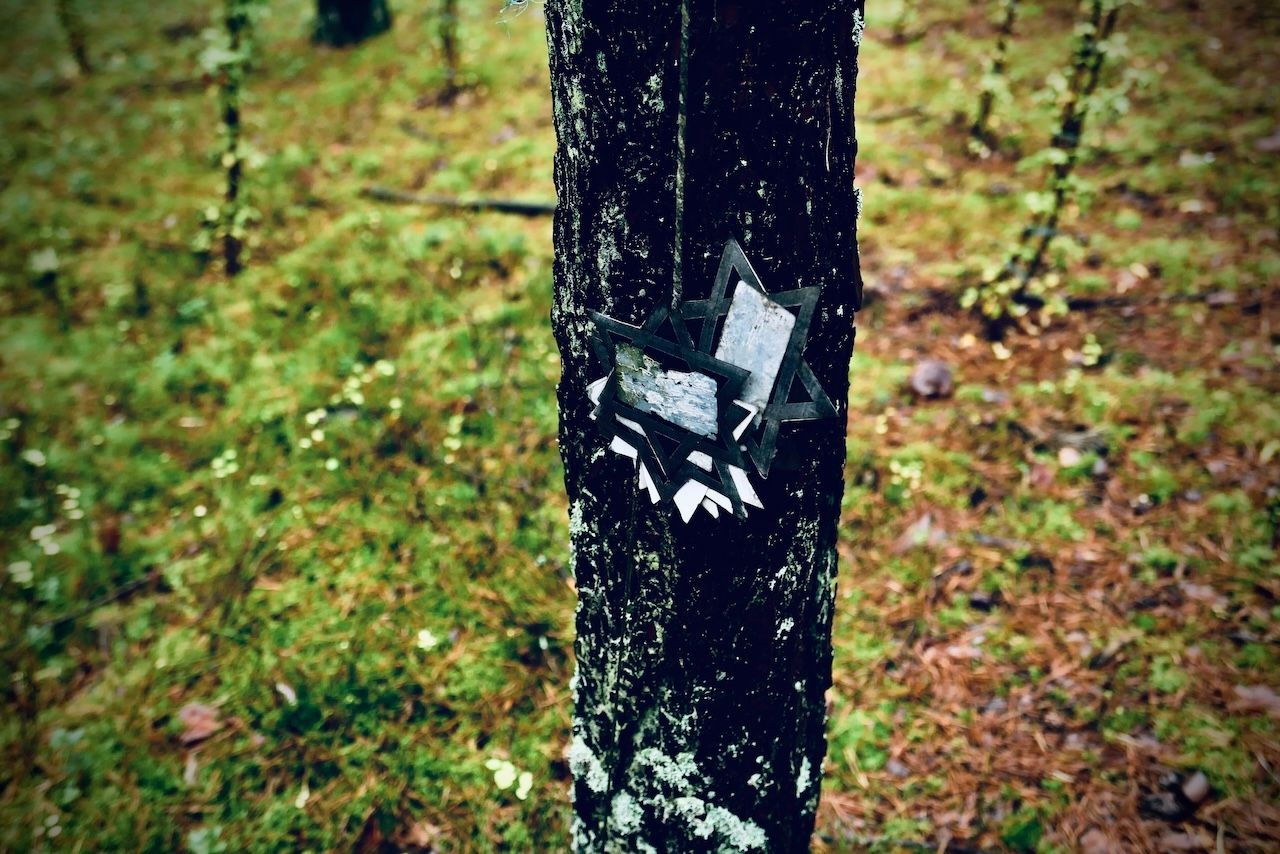

A stone's throw from the Bilgoraj road, the site lies on a gentle slope in the forest. Tall trees stand guard over three mass graves, each humbly indicated by a simple sign and marked off by a low fence. The graves themselves are visible as deep indentations in the otherwise even ground.

The place is quiet. The only sounds being the distant passing of cars, birds in the trees and the dripping of rain water from the branches.

One could easily pass this site by, but for a small stone memorial inviting one to detour into the forest to the actual graves.

Personal Articles | Mass Grave | Jósefów

As I say, visiting such places allows us to honour the memory of the millions of lives lost and pay tribute to those who suffered unimaginable horrors.

These often remote and lonely places bear witness to the immense suffering endured by innocent individuals and in turn offer a unique opportunity to reflect on the consequences of hatred, discrimination, and indifference. By visiting them, we ensure that the victims are not forgotten and that their stories continue to resonate with future generations.

Imagine my horror then, to discover that one of the graves had been very recently desecrated.

The serenity of the moment was ripped away as I struggled to compute that what I was looking at was infact an opened grave, a freshly dug hole of some two meters deep, surrounded not only by sand, but strewn with the clothes, belongings and bones of those shot and buried there.

Articles of clothing, a child's shoe, leather items, a bag, a femur and a pelvic bone among other things spilled unwillingly from the earth and into the present day.

My initial emotion was one of shock, quickly followed by a sense of unease and growing anger. I immediately documented the scene and left to report the crime. I sent my images to HEART (Holocaust Education Archive & Research Team) and my friends at the Sobibor Museum who immediately expedited the information to the appropriate bodies.

(I will try and keep this post updated on the outcomes.*)

But why should I be so afronted by this? Why does it really matter to me?

Well, for me it's quite simple.

Artefacts | Mass Grave | Jósefów

The holocaust was a defining moment in human history, and I firmly believe that it is our responsibility to ensure that future generations understand the magnitude of its tragedy.

Sites like the one in Jósefów serve as powerful educational tools, providing firsthand accounts and tangible evidence of the events that transpired.

Through such visits, we can learn about the causes, consequences, and lessons of the holocaust, fostering empathy, tolerance, and a commitment to preventing such atrocities in the future.

Visiting and maintaining holocaust sites is frankly essential for preserving historical truth.

These places bear witness to the atrocities committed during this dark period, serving as physical reminders of the horrors that unfolded. By protecting and upkeeping these sites, we ensure that the truth of the holocaust is not distorted or denied.

And furthermore, it is through the preservation of these sites that we can challenge revisionism, combat holocaust denial, and safeguard the historical record for generations to come.

The thing is, holocaust sites like Jósefów are not only important on a local level but also on a global scale. They serve as international symbols of remembrance, promoting awareness of the holocaust and its impact worldwide. Simply by coming here we acknowledge the universal significance of these horrific events and their implications for humanity as a whole.

They provide a platform for fostering dialogue, understanding, and collective action against hatred, discrimination, and genocide in all its forms.

Jósefów

For me personally, visiting historical holocaust sites is an essential, personal act that ensures the memory of the holocaust endures and serves as a powerful reminder of the consequences of hatred and intolerance.

In essence, by up-keeping and protecting these sites, we honour the victims, educate future generations, preserve historical truth, and promote global awareness.

It is only through our collective commitment that we can strive to create a world where such atrocities are never repeated.

It seems only fitting then, to end this post by including the Mourner's Kaddish, a Jewish prayer traditionally recited for the dead:

Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world

which He has created according to His will.

May He establish His kingdom in your lifetime and during your days,

and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon;

and say, Amen.

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity.

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored,

adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He,

beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that

are ever spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and life, for us

and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

He who creates peace in His celestial heights,

may He create peace for us and for all Israel;

and say, Amen.

Updates

21.11.2023. Following my notification to the staff at the Sobibor Museum, representatives of the State Museum acknowledged that they were unaware of the situation at Jósefów. They immediately dispatched a team to investigate the site, wrote to the Mayor of the town and engaged with Police. I may yet have to provide a written witness testimony and / or speak further with the guys from the State Museum. I have sent my images and video from the scene to relevant parties.