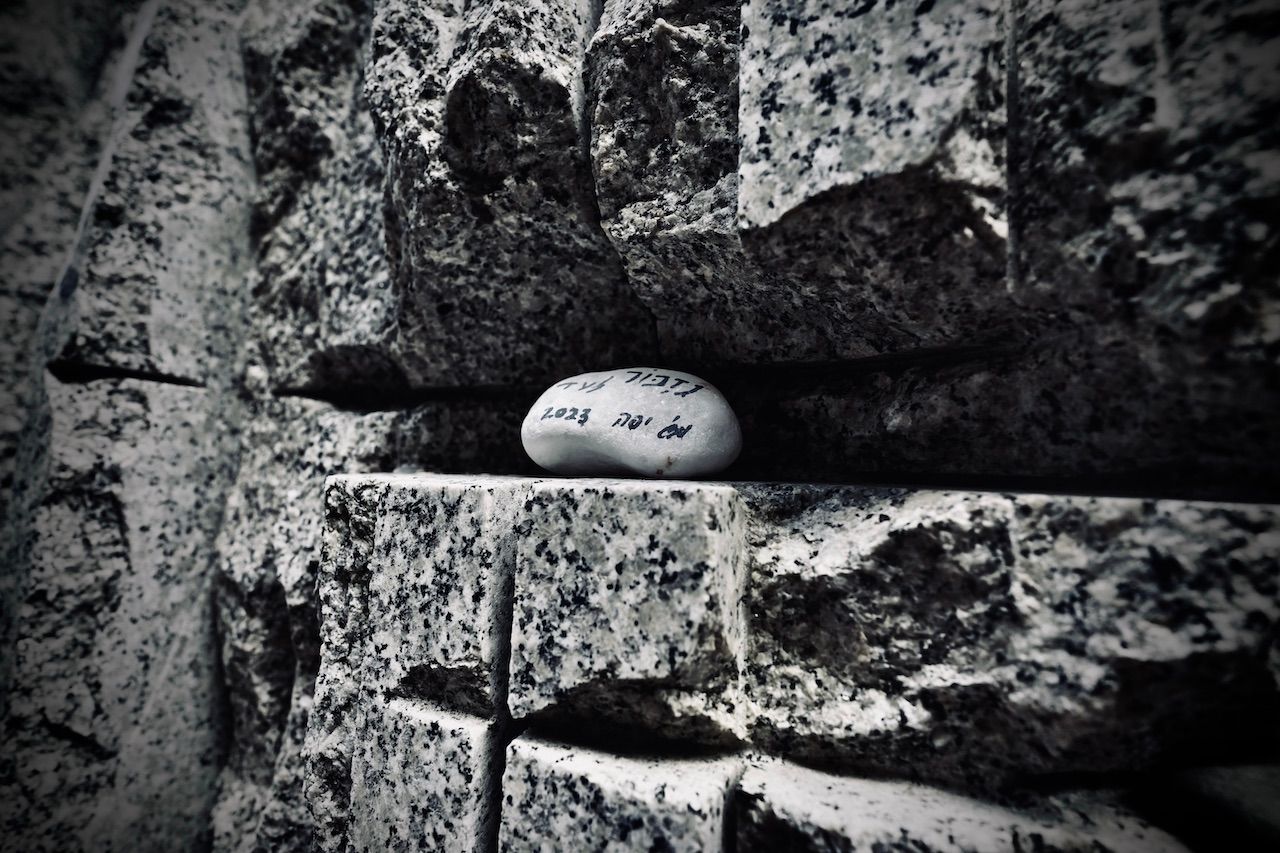

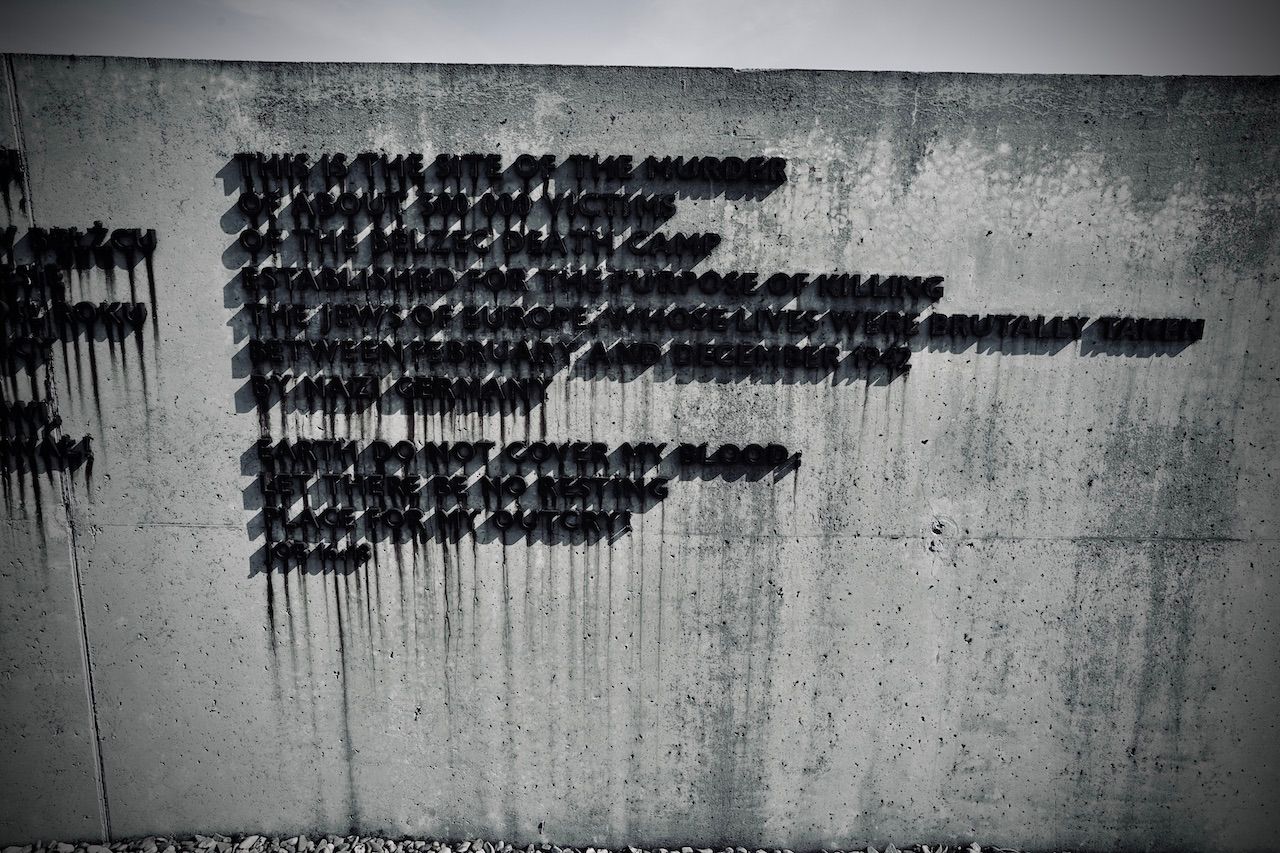

Bełżec, in the far south-eastern corner of Poland, was the first of three Nazi Extermination camps created as part of "Aktion Reinhardt". It operated between 1942/43 and consumed the lives of approximately 500,000 victims, overwhelmingly Jews.

Saturation.

Visiting the memorial today, it is almost impossible to understand what took place here. Precise architecture saturates history, and denies one a true, blinding sense of place.

In this sort photo-essay I have juxtaposed the words of it's only survivor, Rudolf Reder, with my images in the hope of making sense, creating unease and unfolding the tragedy that took place here.

Arrest.

From the testimony of Rudolf Reder.

"Meanwhile, for a few consecutive days, German patrols combed one house after another, looking into every nook and cranny. Some of those caught by the Gestapo had their permits honoured, others did not. All those without permits, or whose permits the Germans did not honour, were driven out of their houses without food or clothing. They found me hiding in a corner, beat me on the head with a stick, and took me away. They squeezed us like sardines into trams and transported us to the Janówska camp. We could neither move nor breathe. Night was already falling. All 6,000 of us were squeezed into a meadow. We were ordered to sit down, and forbidden to move, raise an arm, stretch a leg, or get up.

A watchtower directed its blinding light at us. It became as light as if it were day. We sat there, packed tightly together, young and old, women and children alike. A few well-aimed shots were fired in our direction. Someone got up and was shot on the spot. Perhaps he wished to die a quick death. And so we passed the night. The crowd was deathly silent. Not even women or children dared to cry. At six o’clock in the morning we were told to get up off the wet grass, on which we had been sitting all night, and to arrange ourselves in a column, four in a row.

Our column was guarded on both sides by the Gestapo and Ukrainian police. The Germans began to load the train. They opened the doors to each truck. On both sides of the doors stood the Gestapo men, two on each side, whips in hand, slashing each of us on our faces and heads. All the Gestapo men were alike. They all beat us so badly that each of us had marks on our faces or bumps on our heads.

Transportation.

Women sobbed; children in arms cried. Thus driven along and beaten mercilessly, we climbed on top of one another. The doors to the trucks were high above the ground. In the general scramble we trampled those who were below. We were all in a hurry, wanting to have all this behind us. On the roof of each truck sat a Gestapo man with a machine-gun. Others beat us while counting 100 people to each car. It all went so fast that loading a few thousand people took no more than an hour.We knew that we were being taken to our deaths and that we couldn’t do anything about it. Although all our thoughts were occupied with escape, we saw no possibility of success.

No one said a word to anyone else; no one tried to console lamenting women or to calm crying children. We all knew one thing: that we were going towards a certain and terrible death.

What we all wished for was that it would be quick.

Arrival.

About midday the train pulled into Bełżec.

It was a small station surrounded by little houses occupied by the Gestapo. Next to the station stood a post office and the lodgings of the Ukrainian railwaymen. Bełżec is on the line between Lublin and Tomaszow, 15 kilometres from Rawa Ruska. At Bełżec our train left the main line and moved onto sidings about a kilometre long, which led directly into the camp.

At the main station in Bełżec an old German with a thick black moustache mounted the engine. I do not know his name, but I would recognise him at a glance. He looked like a butcher. He took charge of the train, bringing it into the camp.

The German who brought the train climbed down from the engine in order to ‘help’. With shouts and kicks he drove people out of the trucks...

When the whole train was empty and checked, he signalled with a flag and moved the train away from the camp. Several dozen SS men yelling ‘Faster’ opened the trucks, chasing people out with whips and rifle-butts.

The doors were about a metre from the ground, and the people, young and old alike, had to jump down, often breaking arms or legs. Children were injured and all tumbled down exhausted, terrified, and filthy.

The SS men were assisted by the so-called "Zugsführers", who supervised the Jewish death commando. They were dressed in everyday clothing without any distinctive marking.

Selection.

The sick, the old, and small children - in other words, all those who could not walk on their own - were thrown onto stretchers and taken to pits. There they were made to sit on the edge, while one of the Gestapo shot them and pushed their bodies into the pit with a rifle-butt. There was deathly silence. The Gestapo stood close to the crowd. Everybody wanted to hear them. We all suddenly hoped that, if we were spoken to, then perhaps it meant that there would be work to do, that we would live after all.

The SS spoke loudly and clearly: ‘Ihr geht jetzt baden, nachher werden Ihr zur Arbeit geschickt.’ That was all. The crowd rejoiced; the people were relieved that they would be going to work. They applauded. The crowd was peaceful. And in silence they all went forward: men straight across the courtyard to a building bearing the inscription ‘Bade und Inhalationsräume’ in large letters.

Processing.

I saw that when they were handed wooden stools and ordered first to stand in a line and then to sit down, and when eight Jewish barbers, silent as death, came in to shave their hair to the bare skin, it was at this moment that they were struck by the terrible truth.

It was then that neither the women nor the men - already on their way to the gas - could have had any illusions about their fate.With the exception of a few men chosen for their trade, which could be handy in the camp, all the rest - young and old, women and children - went to certain death.

Little girls with long hair had it shaved; others with short hair went to the gas chambers directly, together with the men. And all of a sudden, without any transition from hope, they were overcome by despair.

There were cries and shrieking. Some women went mad. A dozen or so SS men drove the women along with whips and fixed bayonets all the way to the building and from there up three steps to a hall. There the Ukrainian guards counted 750 people for each gas chamber. Those women who tried to resist were bayoneted until the blood was running.

Eventually all the women were forced into the chambers. I heard the doors being shut; I heard shrieks and cries; I heard desperate calls for help in Polish and in Yiddish. I heard the blood-curdling wails of women and the squeals of children, which after a short time became one long, horrifying scream. This went on for fifteen minutes. The engine worked for twenty minutes.

Afterwards there was total silence.

Disposal.

Then the guards pushed open the doors that led outside. It was then that those of us who had been selected from different transports, in unmarked clothing and without tattoos, began our work.

We pulled out the corpses of the people so recently alive. We dragged them to pits with the help of leather straps while an orchestra played from morning until night.

The camp was surrounded by dense forest of young pine. Although the forestation was thick, extra branches were cut and interwoven with the existing ones over the gas chambers to allow a minimum of light to penetrate.

Behind the gas chambers was a sandy lane along which we dragged the corpses.

Overhead the Germans had put wire netting interwoven with more branches.On a wall opposite the entrance to each gas chamber were more sliding doors 2 metres wide. Through these the corpses of the gassed were thrown outside.

On one side of the building was an adjoining shed no bigger than 2 metres square. This housed the engine, which was petrol-driven. The gas chambers were about a metre and a half above ground level. The doors leading to the ramp, onto which the bodies of the victims were thrown, were on a level with the gas chambers.

I stayed in Bełżec death camp from August until the end of November.

Efficiency.

This was a period which saw the gassing of Jews on a massive scale. I was told by some of the inmates who had managed to survive from earlier transports that the vast majority of the death convoys came during this precise period.

They were coming each and every day without respite. Usually they arrived three times a day. Each convoy was composed of fifty cattle-trucks, each truck containing 100 people. If a transport happened to come during the night, the victims were kept in locked cars until six in the morning.

The average death toll was 10,000 people a day.

Some days the transports were not only larger, but even more frequent. Jews were brought in from everywhere: no one else, only Jews. I never saw anybody else. Bełżec served no other purpose but that of murdering Jews.

Afterwards the engine was turned off. The doors leading from the gas chambers onto the ramp were then opened. Bodies were thrown out onto the ground in one enormous pile a few metres high. The workers who opened the doors took no precautionary measures.

The calls for help, shrieks, and terrible moans of people locked in and slowly asphyxiated lasted between ten and fifteen minutes. Horribly loud at first, they grew weaker and weaker, until there was complete silence.

I heard desperate cries in many different languages.

They were all gassed.

When, after twenty minutes of gassing, the guards pushed open the tightly shut doors, the dead were in an upright position. Their faces were not blue. They looked almost unchanged, as if asleep. There was a bit of blood here and there from bayonet wounds. Their mouths were slightly open, hands rigid, often pressed against their chests.

Those who were nearest to the now wide-open doors fell out by themselves.

Like marionettes.

Examination.

Before they were murdered, all the women were shaved. While the first group was rushed to the barracks, others waited their turn, naked and barefoot even in winter and snow. Lamenting and nearly mad mothers pressed their children close.

Each time I watched them with a bleeding heart. I could not really stand the sight of them.

A group of women already shaved was hustled along, while those who followed waded through the hair of many shades which covered the entire floor of the barracks like some soft and silky carpet. When all the women had been shaved, four workers using brooms made from the branches of lime trees swept the floor and collected the hair into a large pile the size of nearly half a room.

In those few hundred metres separating the gas chambers from the pits stood some dentists with pliers. They stopped everyone as they dragged the corpses away. They opened the mouths of the dead and yanked out the gold teeth, which they then threw into baskets.

We dug pits, enormous mass graves, and pulled bodies along. We dug with spades, but there was also a machine which loaded sand, brought it to the surface, and emptied it beside the pits.

There was a mountain of sand which we used to cover the pits when they were filled to overflowing. On average 450 people worked round the pits on a daily basis. What I found most horrible was that we were ordered to pile bodies to a height of about a metre above ground-level, and only then to cover them with sand.

Thick, black blood ran from the mounds and covered the whole area like a sea. In order to get to the next empty grave we had to cross from one side of an already full pit to another. Ankle deep we waded through the blood of our brothers. We walked over mounds of bodies. And this was most dreadful, most horrible.

Besides digging graves the commando was also employed in emptying the gas chambers, piling the bodies on a ramp, and dragging them all the way to the pits.

The ground was sandy.

Two workers dragged one body.

We had leather straps with metal braces, which we put round the hands of a corpse. Then we pulled, while the head of the dead man often dug deep into the sand . . .

As regards small children, we were ordered to carry them in pairs on our backs. If we dragged the dead, we did not dig graves. When we dug graves we knew that thousands of our brothers were being murdered at the same time.

The SS men ordered an orchestra to come to the courtyard and await further orders. The orchestra, composed of six musicians, was in its usual place on the path between the gas chambers and the pits.

The musicians played on instruments which had belonged to the victims.

The SS men ordered the orchestra to play ‘Everything passes, everything goes by’ and ‘Three lilies, comes a rider bringing lilies’

Mathematics.

The Germans calculated that they had to keep aside 100 men - already naked - to help with burying the murdered, who were too numerous for the death commando to manage in one day.

They chose young boys only.

Whipped and bludgeoned, the boys dragged corpses to the pits, naked in the snow and cold, without even a drop of water. In the evening an SS took them to the pits and shot them one by one with a pistol. He ran short of bullets for the last few, so he killed them with the handle of a pickaxe.

I did not hear them moaning, but I saw them trying desperately to jump the death queue, tragic and helpless relics of youth and life.

There, staring blankly into the depths, with a lunatic gaze in their eyes, stood old people, children and the sick, all waiting to be shot.

They had been given plenty of time to see the corpses, to breathe the smell of blood and putrefaction, before they were shot.

Words are inadequate to describe our state of mind and what we felt when we heard the terrible moans of those people and the cries of the children being murdered.

Three times a day we saw people going nearly mad. Nor were we far from madness either. How we survived from one day to the next I cannot say, for we had no illusions. Little by little we too were dying, together with those thousands of people who, for a short while, went through an agony of hope.

Apathetic and resigned to our fate, we felt neither hunger nor cold. We all waited our turn to die an inhuman death. Only when we heard the heart-rending cries of small children - ‘Mummy, mummy, but I have been a good boy’ and ‘Dark, dark’ - did we feel something.

...

Disappearance.

After several months in Bełżec, off I went in a lorry with one guard and four Gestapo to procure supplies.

After loading the whole day, I stayed in the lorry guarded by one of the thugs, while the others went away looking for fun. I sat there for a few hours without moving or thinking. Then, quite by chance, I noticed that my guard was asleep and snoring. Instinctively and without a thought, I slipped down from the lorry and stood on the pavement pretending to adjust the load.

Then I slowly backed away.

Legionowa Street was full of people.

There was a blackout. I pushed my cap down lower and no one noticed me. I remembered the address of my Polish housekeeper and went straight to her flat. She hid me.

It took twenty months for 26 the physical injuries to heal.

When the Red Army expelled the Germans from Lwów, I was seized by a desire to go back to this place where two and a half million of our people met their terrible death.

Return.

I went there soon and spoke at length with the locals.

They told me that in 1943 a much smaller number of transports came to the camp. The murder centre for the Jews moved further west, to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

In 1944 the Germans opened up the pits and burned the bodies with petrol.

Dark, heavy smoke rising from the enormous open-air pyres hung over an area of several dozen square miles. The wind carried the stench still further, for many long days, nights, and weeks.

And later, the locals told me, the Germans pounded the remaining bones to powder, which the wind blew away over the fields and forests.

When the production of ‘artificial fertiliser’ from human bones came to a halt, the open pits were filled with soil and the blood-soaked earth scrupulously levelled.

The German murderers covered this graveyard for millions of murdered Jews with fresh greenery.

I said goodbye to my informants and went along the familiar siding.

The railway line was gone.

Through a field I reached a young and sweet-smelling pine forest.

It was very still.

In the middle of it was a large, sunny clearing."

Context (Video).

Camera: Sony A7ii

Simulation: None

Retouching: Dramatic & Adjustments

You might also like: